Those Who Feel the Fire Burning

Drone Perception and the Aesthetico-Political Image

On Pontecorvo’s holocaust film Kapo, Jacques Rivette once said that the least one can say is that it’s difficult, when one takes on a film on such a subject, not to ask oneself certain preliminary questions. Not doing so, he notes, can only be indicative of negligence, of some sort of ignorance (Rivette). What is at stake, and which Rivette reproves Pontecorvo for, is the approach to the subject matter, that is, an ethics that spans the subject filming, to the subject filmed, to the subject spectator – and, Serge Daney adds, involving a certain distance therein (Daney 2004). Pontecorvo’s tracking shot imbues the image with a certain realism, and in that realism the abject choice is made, Rivette claims:

Look however in Kapo, the shot where Riva commits suicide by throwing herself on electric barbwire: the man who decides at this moment to make a forward tracking shot to reframe the dead body – carefully positioning the raised hand in the corner of the final framing – this man is worthy of the most profound contempt.

Rivette condemns Pontecorvo for attempting to make of something so horrendous something beautiful, to let the tracking shot actually show that which cannot be shown with a certain grace. The negligence, in Rivette’s view, lies in not just the final shot, but in the tracking towards it, framing a movement that results in a spectacularized image. This is an abject thing to do according to Rivette. He thus emphasizes the importance of how to approach such, or any, subject matter. There must be a certain responsibility from the subject filming, to the subject filmed, to the subject spectator – in short, in the constellation of the image. In other words, Rivette emphasizes the importance of a responsibility before the image.

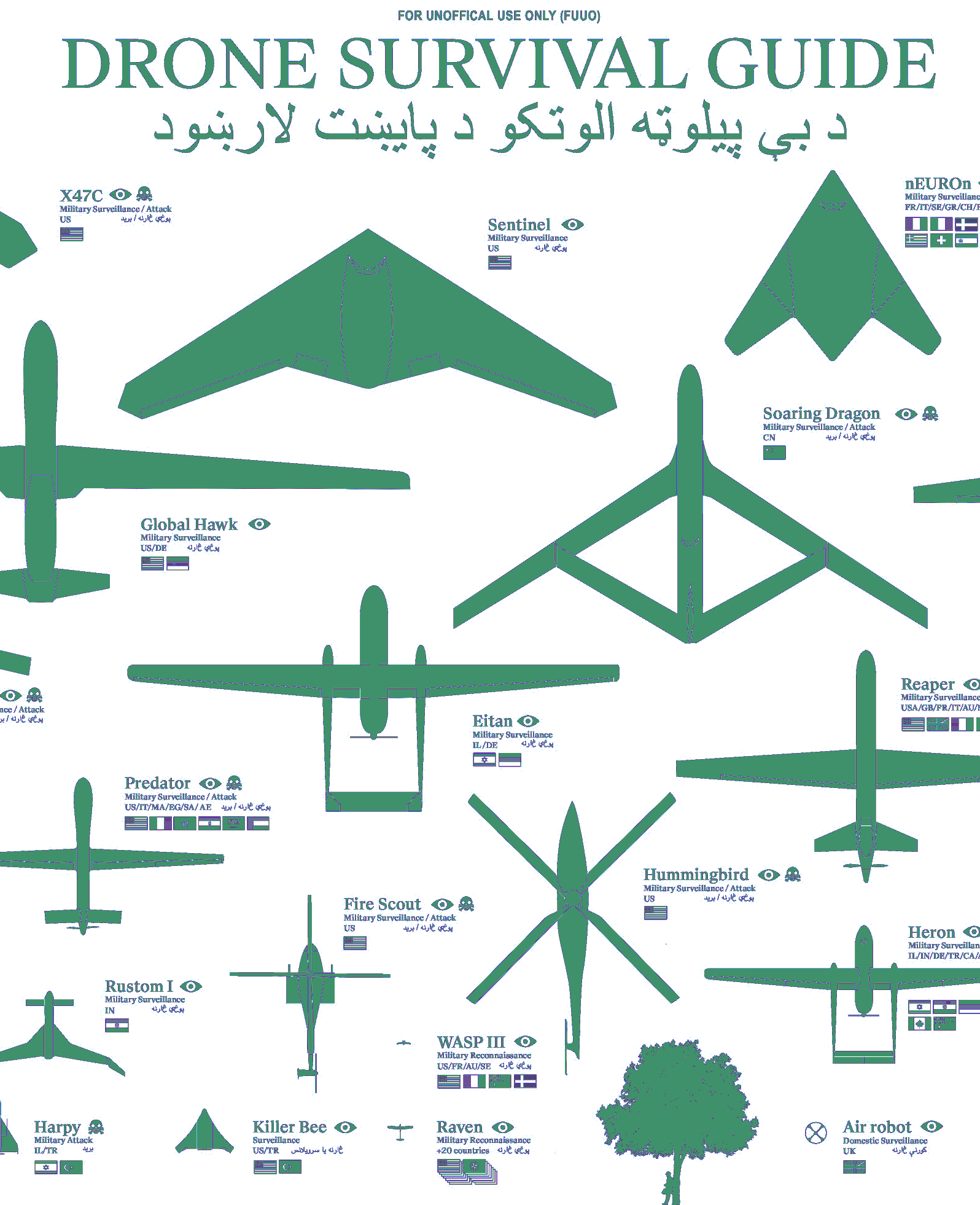

The approach of Those Who Feel the Fire Burning (2014; hereafter Those Who), young director Morgan Knibbe’s new film, is thus considered remarkable to say the least, perhaps even questionable. This film shows the lives of a family of refugees making a dangerous passage to some other place – presumably Europe, given the current influx of refugees, although the film never makes this explicit. We do not know where the family came from, we do not know where their journey is going, nor do we know where they reside as the film subsequently follows their daily lives after the journey. More poignant than this refusal of localization, however, is precisely how the film approaches its subjects. Those Who is for the most part shot with a drone camera, in itself an already remarkable choice given that the drone is a known surveillance tool and in some cases even a weapon. The choice of a drone makes the film strikingly impersonal from the outset, and this impersonality is only further emphasized by the drone’s specific movement: its swerves and the subsequent erratic line of perception created in its flight, lead to a rather unusual and perhaps inappropriate way of filming the refugees. There is very little direct attention and thus little space for the refugees as subjects; the drone, and with that the camera, more often than not turns away from the refugees at the most unexpected moments. The refugees thus become but parts of an environment that the camera registers in flight and so the line of perception makes for a certain distantiated approach. One can question whether this is, ethically speaking, proper considering the situation of these people. Ought there not to be given more space to the subjects themselves, their stories, their experiences? Is the turning away from the refugees, albeit due to the drone, not irresponsible to the subjects filmed, and thus irresponsible towards the image in the way Rivette meant?

Director Knibbe insists that he did not want to make a political statement of any sort. What the film ought to be, he stresses, is an experience, no more, no less (Knibbe 2014). Such an experience, one could assert, would have to be autonomous. French philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari call such an autonomous experience as such a sensation; a sensation would be, they argue, self-posited, an expression of pure immanence (1994: 172). A sensation of this kind is free from the restraints of communication, free of any sorts of universalization – it emerges within the constellation of the image, between the three subject positions, being determined by it, but not determinative of it. That is to say, following the reasoning of Deleuze and Guattari, an image as sensation does not depend and fall back on one or the other, it is not a product of either. Rather the image in itself is a production in itself, a creation, and implores to be taken as such.[1] The responsibility before the image that Rivette uncovered can, in this line of thinking, be seen as a commitment to immanence, a commitment which takes responsibility for what an image is in its creation.[2]

To create such an image does not mean it ought to be an abstraction that is free of any form or subjectivity; on the contrary, as it finds its emergence “in-between” it might avoid the image in any way becoming determinate of the forms or subjects, but it is not undetermined by any either. Communication, Deleuze and Guattari tell us, will always tend towards a universalization (1994: 9). Such universalization could, for instance, turn into a political statement and be determined or appropriated by specific ideological means. It could also lead to a subjective account, relegated to the realm of mere fiction. Any sort of universalization through communication would draw the image towards one side of the constellation, consequently ending up denying any of the other side its prevalence. An image as sensation creates, in every instance, a new reality. Thus it is surely determined by its conditions, but it does not in turn determine them.

In what follows the improbable conjunction of the impersonal perception of drones with the precarious subjects that are shown in Those Who is further explored. Through the philosophy of Deleuze and Guattari the notion of the image as self-positing will be analyzed in how it works. This will be done in terms of a line that is construed in Those Who. This line is one of perception in that it is in a near-constant flight, giving almost no space to thought as the movement keeps going. The line is marked by a specificity, namely what comes forth from the drone’s motility in combination with the attunement to it by the subject filming, amounting to certain swerves. Thus what is at stake here, and what can be considered a distinction to the many already existing analyses of drone perception, is the specificity of the movement that can occur with drone filming and what potential this movement holds. What will then be put forward is the contention that by making operative that which is specific in the objective movement of the drone, these swerves suspend the subject-object relation. In so doing, the film excavates that which is at once determined by the constellation, while at the same time being undetermined as it forms a self-posited image. Finally, the political of such an image will be considered.

A flight between fiction and reality

To start with a fictional scene might be the only way to show what would otherwise be nearly impossible, or unethical, to show. In Those Who the opening scene – wherein we find a family trying to cross an unspecified ocean – is one that attempts it nonetheless. It attempts to make us witness to the perilous journey that is undertaken.[3] But it is dark during the crossing, so there is little that one can actually see. The water can be heard crashing onto the boat, and only by some light coming from a flashlight can the shapes of the different family members be seen. As the waves become too strong disaster befalls the family, and the grandfather, through whose point of view we have witnessed the event, gets thrown overboard and is taken by the water. Slowly submerging, the little visibility that there was gets drawn into the complete and utter darkness of the depths.

It is from this darkness that a line of perception emerges. Having drowned, the spirit of the grandfather takes flight, leaves the water and begins to dwell the family’s place of refuge. The flight, still from a point-of-view shot, constitutes a line no longer bound by earthly restrictions, and becomes a line of perception in continuous flight, never allowing any grounding. The scene itself, with its near impossibility of actually seeing what happens, gives but an impression of events, emphasizing the impossibility of going any further in such a depiction. The event is necessarily fictionalized, for besides any ethical concerns it is impossible to actually film something like this. But it is this fiction that imbues the image with the possibility of giving an impression. That is to say, it is via this fiction that the film finds a possibility to give an impression of such an event, and the impression is affirmed in the fullest when the line takes flight, embracing its fictional nature. All the while it remains but an impression it does not go further in representing the event as perception cannot get a hold of it in the dark. It never pretends to more than an impression. The line of perception is where the fictional and the flight of the drone come together.

After it has taken flight, the line of perception does something other than remain in the fictional, for it tends towards those who have survived the crossing, towards the living, and there it occasionally grounds itself again. Their situations are observed as the spirit keeps dwelling, as it keeps moving from one survivor to the other. Ultimately, it finds each of the remaining family members – or so it insinuates – in their daily lives after the crossing, as the line of perception glides from one to the other. Here the fictional and actual meet as the fragments impose a certain realism on the image again and ground it. The line of perception then moves in between the unreal and the actual, or, literally, between the spiritual and the material (Bergson, 2004: 1).

What makes the line of perception actually go in between the unreal and the real is not the mere move from the real (the boat scene) to the unreal (the taking flight of the spirit) to the real again (the scenes of the daily lives of the survivors). Solely this kind of movement would maintain a certain gap between the different states, making the image that fills the gap therefore remain dependent on the different states. Deleuze in his cinema books calls this gap the interval, or that which maintains a difference between perception and action. If the interval remains intact, Deleuze argues, the in-between remains a difference between two things instead of a for-itself. Any image produced would be a correlate of either thing. Likewise, any thought that is produced by the line, in being dependent on perception, would do nothing but trace it, that is, in a docile manner thought would always be subjugated to the line. Or worse, thought risks falling back, completely severing the line, resulting in simply nothing. What is to keep thought from doing either?

Elsewhere, Deleuze and Guattari refer to this interval as that which separates being and thinking – a separation that makes us ‘the slow beings that we are’ (Deleuze and Guattari, 1994: 36). What is at stake here is thought itself, always lagging behind being, that is, behind action. The interval however, Deleuze and Guattari contend, can be traversed, if, and only if, thought and being fall together. Falling together would compose a movement that is both impersonal (for being can no longer be its ground) and singular (for thought becomes per se different): the self-positing force of pure immanence (Deleuze, 2001: 28). The impersonal singular, if composed in Those Who, would be the emergence of an image that is self-positing, of one that avoids the universalization of communication. It would hold a responsibility before the image insofar as it maintains sufficient distance within the constellation of the image. The question is then, how does this occur if simply shifting between real and unreal does not suffice? Or phrased differently, how is the interval traversed?

Assemblage

To understand how the interval is traversed means understanding how the interval is constituted in the film in the first place. This, initially, means dealing with the problem of representation. What Deleuze makes explicitly clear on that account is that cinema is not naturally bound to a logic of representation: ‘cinema does not give us an image to which movement is added, it immediately gives us a movement-image’ (Deleuze, 2005a: 29). It is not an image of movement that cinema produces, it is movement itself. What keeps cinema within the logic of representation then lies within the conditions of thought rather than in the cinematographic apparatus itself, meaning that an image is not per definition tied to such conditions, it becomes so by the way it is given form within the constellation of the image (thus the subject filming is here considered imperative, i.e. in its mannerism.)

Deleuze argues that filming goes by way of what he calls an assemblage, or a ‘distributed system comprising sentience, memory, and communication’ that ‘begins to act as an extension of the self’ (Shinkle, 2015: 4). There exists something of a camera consciousness, a certain feeling with the camera, Deleuze says. ‘We are no longer faced with subjective or objective images; we are caught between a correlation between a perception-image and a camera consciousness which transforms it’ (Deleuze, 2005a: 74). Perception is extended from the subject filming to the camera, from subject to object – the subject filming and camera inform an assemblage, where through-perception is extended. Perception with the camera is then not ‘defined by the movements it is able to follow or make, but by the mental connections it is able to enter into’ (Deleuze, 2005b: 23). Thus perception can be ungrounded from its conventions or its conditions by entering into new connections. Moving between the human and its technical counterpart, it can find new ways of seeing and concomitantly new ways of thinking. The new perceptions that find their genesis in specific movements are then precisely the impersonal singulars.

Specificity

Those Who’s specific movement likewise relies on the assemblage that is informed by the technique of filming as operationalized. The flight of perception that emerges is one that comes from a camera mounted onto a drone, allowing for enormous degrees of freedom, for the gliding and its accompanying swerves and ultimately for a certain consistency between them. As McCosker notes on drone movement, ‘[t]he drone’s motility is “autonomous” and has “self- sustaining vertical and lateral movement”’ (McCosker, 2015: 3). As the drone is controlled from a distance, its image is thus immediate yet disembodied – disembodied in that the movements it creates are strongly mechanical. There is an assemblage informed by the relation of the subjective and objective, and even though disembodied, the subject is extended in this manner. Drone perception’s specificity is then precisely a disembodied extension.

The movement that is produced through this disembodied extension of drone perception in Those Who is in the first place marked by its swerves. That is, what makes the movement specific is precisely the swerve in combination with the continuous self-sustaining vertical and lateral, stabilizing movement. Whence minimal divergences are determined within its continuous stabilizing, being intrinsic to the drone perception.

In one particular scene in Those Who this specificity is foregrounded in a poignant manner. As the camera is hovering, trying to maintain a focus on two of the refugees sitting at a table playing a game of cards while remaining silent, the alteration of movement occurs at the exact moment one of the two begins to speak. As if the minor vibrations of the voice unsettle the balance and stasis of the drone, an abrupt swerve occurs and the drone reorients: in a swift movement, to the back upper corner, making a near complete turn on its axis while simultaneously bobbing upwards and accelerating towards that exact corner, the drone finds its stasis and focus again. It then perceives the relief of the white ceiling and a cockroach slowly making its way across it. Marking this scene is the unexpectedness of the swerve, which, however minor the divergence may be, determines the perception of the camera. Thus instead of focusing on the two men at the table, especially when they finally begin to talk, the camera shows completely other things.

It is through these minimal divergences, or swerves, that a wave-like movement with a full three-dimensional possible distribution is composed. In a sense the movement might take a completely different direction at any given moment. And the attempt to keep the drone flying ends up emphasizing this exact alteration of direction. In this way the technique of flying with a drone is marked by the attunement to its movements. In other words, what in part determines the drone perception is not so much what the subject filming wants to see, but rather that it can see at all by keeping it in stasis. And in line with the assemblage, this process of attunement takes place before any conscious reaction; it is the continuous reevaluation of the relation between the subject filming and the camera, thus the maintaining of the disembodied extension.

The swerves that occur due to this attunement are, according to Deleuze, exactly what he calls minimal indeterminacies (Deleuze, 2004: 306). That is, ‘[t]his minimum expresses the smallest possible term during which an atom moves in a given direction, before being able to take another direction as the result of a collision with another atom.’ (ibid.) It is neither the weight of the atom nor the void they are in that is responsible for their direction and velocity, it is the swerve itself as ‘a synthesis which would give the movement of the atom its initial direction’ (ibid.). Taking the notion of the swerve from Lucretius, one of the ancient Epicurean philosophers, Deleuze argues that the swerve, similar to how it occurs in Those Who by virtue of the attunement, is itself the reason for a singular alteration in movement. It makes the movement of the drone perception neither dependent on its subject filming nor on its objective camera, but places it in-between.

In this capacity, in attuning to and thereby emphasizing the swerve, the flight is erratic: it takes on new directions abruptly to follow these through, until at indeterminate moments yet another direction is taken. The movement hence constitutes a line insofar as there is a persistence to this erratic flight.

Interstice

In its persistence the line of perception continuously makes new relations to the whole, that is, the film. The swerves and their minimal indeterminacies play a crucial part in shaping the narrative and more. When the camera by virtue of the swerve unexpectedly starts tracing the cockroach on the ceiling instead of the refugees at the table, this shapes the narrative. As a matter of fact, these minimal indeterminacies turn out to play a rather determining role in regards to the whole, as indeed the expected movement of filming the refugees becomes interrupted frequently enough. More often than not, the camera will show the surroundings, focusing in on seemingly unimportant details. Ultimately, the entire line drawn isthen the narrative of Those Who Feel the Fire Burning. Interestingly, thought or that which takes shape, are then dependent to a large extent on precisely these movements. In effect, that what Deleuze called the interval, the relation of thought and being, is here pushed to a limit.

To understand this relation in depth it helps to lay two similar movements in terms of motility, and above all of in terms of a line of perception, alongside that of Those Who. The first being Wim Wender’s Der Himmel Über Berlin (1987), and the second Gaspar Noë’s Enter the Void (2009). Both films also construe a line of perception by virtue of a flight, so in each we can equally speak of thought trailing behind perception. However, both films also posit a different relationship to the whole.

In Der Himmel, and in particular its opening scene, there is a motility that glides from the highest building downwards along the walls of apartment buildings, into windows and rooms, and back out onto the street. This movement has, in contrast to that of Those Who, a less erratic line, smooth even, as it gently glides downward observing all that it passes. The descent marks the desire of the angel protagonist to become an earthly dweller, thus going from the highest point atop a skyscraper all the way to the streets. Thought is here positioned between two points, from the heights and angelic world to the down-to-earth street and human world, and thus it is framed between these two points. In other words, it is subjugated to the given points, and determined by them. Thus the smooth glide downwards allows a continuous correlation between perception and thought, maintaining the interval as thought is subjugated to the movement.

The difference here between the line of perception that is construed in Der Himmel and Those Who lies not in the starting point, for they share that in a way, though in inverse (for in the former it is a descending one, and in the latter it is an ascending one). Rather, the difference lies in the line’s enclosure. In Der Himmel the descent ultimately results in a grounding of the line, where it loses its motility and thus gets framed. Moreover, this framing is already given from the start, as it marks the angel’s desire. In Those Who such framing never occurs, as the line keeps tending towards the middle of the real and the spiritual. What marks the line of the ghost here is not a unidirectionality, but rather a double as the movement keeps ascending but at the same tries to ground itself in the daily lives of the survivors.

Enter the Void construes a similar line of perception and a subsequent relation to the whole, yet under completely different conditions. Here the line of perception is intermittently interrupted by its moving into different strata of time. As the flight traces the afterlife of its recently deceased protagonist, an occasional flash of memory is triggered by whatever the line of perception encounters. Though the line of perception is certainly erratic, as it seemingly moves around undetermined, the small interruptions of memory stop the incessant movement and allow thought to find its ground again. Every interruption that invokes a flashback halts the erratic line and contextualizes it in terms of narrative. In other words, the line loses its autonomy and becomes once again grounded in the other spaces that are the memories. Though certainly the erratic line of perception expands the interval due to its temporary insistence and erratic nature, at each interval it becomes subject to that which is given by the memory-flashes – in other words, it gets grounded again.

Any such form of actual grounding never occurs in Those Who. Instead the line perpetuates a certain violence upon itself in its insistence to keep going. Even though there will be cuts – as the film is certainly not one long line of flight by the drone – these cuts become subjugated to the line because it keeps on extending. In drawing its erratic line, gliding from one survivor to the other, there is a sheer persistence that marks this line of perception, one that is indifferent to its surrounding and turns into pure endurance. In enduring, the line of perception omits or dissolves any intention or objective, and its movement becomes its own constituent of direction and speed.

That line drawn in Those Who ungrounds thought as it falls behind trying to follow the erratic dispersions of movement. It ungrounds any points or states wherein thought could possibly find its shelter, its needed stasis or state. In that manner thought, that has need for such points of extrapolation or states of recognition, falls behind to such an extent that it opens up to what Deleuze calls an interstice: the interstice is not one or the other, it is the “between” (Deleuze, 2005: 174).

Consistency

What endures becomes that which persists within the interval. Within the interval, the question becomes how do things stay together, how do they refrain from falling into pure chaos?[4] How does thought refrain from falling into pure chaos, to withdraw from the line and reinstate the same?

Here the swerves gain function. It is through the swerves, through the minimal divergences they introduce, that thought does not fall back into the void, but gets folded out onto the line of perception. In other words, at each occurrence of a swerve thought does not have time to catch up, as it were in Enter the Void, but rather it is shocked and whipped up to unfold onto the line of perception. Thus each of the swerves does not introduce an insurmountable distance wherein perception dissipates; rather, it is forced to make a new connection as it is folded inward onto perception itself. What would not belong to the whole becomes part of it by virtue of the divergence that the swerve introduces: the cockroach on the ceiling becomes of equal importance as the two men sitting at the table playing a game of cards; the cars on the street that are followed when the camera makes a sudden jolt outside become of equal importance as the men inside the apartment.

The unfolding is the precise process of mutual inclusion, or “the simultaneous adoption of and distance from”, as philosopher Brian Massumi calls it (Massumi, 2014: 46). So instead of falling back into chaos or adapting to a distance that introduces a break or cut, the swerves introduce a consistency to the line whereupon the interval is traversed. Within mutual inclusion there is no longer any determining factor that is outside of the constellation. The mutual inclusion marks the swerve as being by no means a contingency, rather it is how “there is a unity of causes among themselves”, among the parts that make up the assemblage (Deleuze, 2004: 307). There is then no longer something else determining what the movement produces, but rather it becomes self-positing, a consistency in and for itself. When and if such consistency is attained – for it needs to be stressed that this all but a certainty, since it can happen anywhere in the line (Deleuze, 1998b: 158) – the line of perception becomes a line of flight, “a path of mutation precipitated through the actualisation of connections among bodies [or assemblages] that were previously only implicit (or ‘virtual’) that releases new powers in the capacities of those bodies [or assemblages] to act and respond” (Lorraine, 2010: 147). It is a line of flight for it produces something that is singular because it is undetermined, yet is determined by all of the parts.[5]

Desubjectification

By virtue of the line of flight that Those Who invokes, space becomes homogeneous taken from the point where movement passes through, or heterogeneous taken through the duration of the movement where space is continuously informed by it. There is no privileged space, no particular focus attached to something that can turn into a linear line, like a story or an even less structured form: the space is an any-space-whatever (Deleuze, 1995b: 44). Subjects are decentered, as they are in this space but epiphenomena; they are continuously informed by the movement of the line. As with the above described scene: a man alongside a cockroach, alongside a busy street and a blinding streetlight, alongside a shimmer of the moon in a reflection. Or when the line of perception takes us into a mosque, which some of the refugees attend to: the people on the floor praying alongside the decorated walls, alongside the large chandeliers, alongside the mosque’s pillars. The subject or subjects are but part of the whole at best. More often than not, one cannot even speak of a subject but merely of a body, as the subject does not have any space for existence. There is no privileged room for being a subject here.

Desubjectification is not a kind of salvation; on the contrary, it is the pain of not being a subject; or at times even the pain of having to become a subject every day. Nor is the middle a place of careless joy; on the contrary, it is where subjects are near to death, where subjects are marked by lines their bodies can barely sustain. The people as sovereign subjects are missing in the at-once terrifying and consuming darkness of the middle. And people actually go missing in that darkness, as did the grandfather of the family in the starting scene whence the line emerged. It is the painful realization of the middle. It is the painful realization of people living in between life and death, desubjectivized in being subjected to the situation. It is also the realization of the impression that was given in the opening scene, where what was impossible could only be approached. The real and the unreal come together in the line of flight, in the double movement wherein thought and being fall into infinity. None is dependent on the other; they are absolute and real. And in this real, the people are missing: they are no longer in their countries, instead residing in these in-between spaces – the most poignant example of life in between. This is the thwarted logic of the current geopolitical state of things. But this “acknowledgement of a people who are missing is not a renunciation of political cinema,” Deleuze writes, “but on the contrary the new basis on which it is founded” (2005b: 217). There is necessity for political art precisely because the people are missing.

What can emerge from this darkness – and this is the responsibility to the image in a manner of Spinozean ethics, such as Deleuze and Guattari maintain – is the possibility for an image to be self-posited, to be immanent to itself. What emerges from the dark in Those Who is a line that, albeit marked and often terrifying, might find an opening within the conditions of perception. To be able to alter the conditions of perception, allowing a place for thought that is not given but existent only in terms of its own grounding. What Deleuze here sees as the locus of modern political cinema is the need to circumvent identity politics, making it at once both possible and impossible, and to create space for a new people.[6] That is a politics that precedes being (Deleuze and Guattari 1980: 203). But it is not politics that ignores or negates the subject.

Politics of the image

What precedes being is how the image is created in Those Who; how it is a sensation in and of itself. It is such in excavating the impersonal that lies within the constellation. In a sense, the drone still marks death, as it does in terms of being a weapon or a spying tool, but here it marks it not in the capacity of so being, but in its relation – both with the subject filming, where the impersonal is constituted by the attunement to the swerve, and with the subjects filmed, where the impersonal is constituted by its turning away. In this double movement, which therein maintains a consistency, the perception is turned onto itself, exposing precisely the impersonal relation in itself, as a sensation.

The specific movement is tainted by darkness. Being a subject herein becomes impossible. Yet in the same movement, or rather in the persisting of that movement, the line also draws a line of flight. This, the line of flight, is exactly the sensation in itself, as it uncovers what is impossible and draws it into the real. It adds something to perception, to thought, and that is the space it can give for the subjects filmed. Not as subjective space, but as a possible space wherein they might become subjects.

Rivette called the specific movement in Pontecorvo abject because what it did was frame its subject, to subject it to a certain emotion, whilst being something that can never do justice to the subject it is supposed to represent. This problem is undercut in Those Who. The tracking does not stop, it persists and goes in-between where it excavates the pains of desubjectivication while rendering it real in affective terms.

This is not to say that this approach is how it must be done. On the contrary, the approach and the image are specific to the constellation wherein it emerges. That means it is both subjective (as in taking into account the subject filming and the subjects filmed) as well as objective (as in taking into account the technological apparatus.) It is just that at these specific moments of the swerve, which introduce minimal indeterminacies, the determinative of either subject or object are temporarily suspended. It is then that an impersonal singular can emerge within the constellation of the image, being determined by it and thus retaining a sense of particularity. But in being singular, in the new relation it engenders, it does not become determinative of the constellation, that is, it in no way falls back onto its constellation; rather in the suspension it leaps forward, grasping that which marks the relation, engendering possible new thought. That is a responsibility before the image.

A politics of the image thus considered lies then in a commitment to immanence, wherein one searches, (much like Morgan Knibbe does), for ways not just to stay true to oneself, the subjects one is filming, or the subject viewers, but rather to the image and its creation of a reality. This is where the responsibility of the act of filming lies, which falls together with the possibility of creating space via that means. In so doing, the politics of the image precedes being, can take responsibility for being.

References

Bergson, Henri. 2004. Matter and Memory. Translated by Paul, Nancy Margaret and Palmer, Scott W. New York: Dover Publications.Daney, Serge. “The Tracking Shot in Kapo.” Translated by Laurent Kretzschmar. In Senses of Cinema, April 2004.

Deleuze, Gilles. 2005a. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. Translated by Tomlinson, Hugh. London: Continuum.

Deleuze, Gilles. 2005b. Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Translated by Tomlinson, Hugh and Galeta, Robert. London: Continuum.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1988a. Spinoza Practical Philosophy. Translated by Hurley, Robert. San Francisco: City Light Books.

Deleuze, Gilles. 2004. The Logic of Sense. Edited and translated by Boundas, Constatin V. London: Continuum.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1998b. “Exhaustion.” In Essays Critical and Clinical. Translated by Smith, Daniel W. and Greco, Michael A. London: Verso Books, pp. 152-174.

Deleuze, Gilles. 2001. “Immanence: A Life…” In Pure Immanence: Essays A Life. Translated by Boyman, Anne. New York: Zone Books, pp. 25-34.

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. 1980. A Thousand Plateaus. Translated by Massumi, Brian London: Continuum.

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix. 1994. What Is Philosophy? Translated by Burchell, Graham and Tomlinson, Hugh. London: Verso Books.

Deleuze, Gilles and Parnet, Claire. 2007. Dialogues II. (trans. Tomlinson, Hugh and Habberjam, Barbara) New York: Columbia University Press.

Hardt, Michael. 2002. Gilles Deleuze: An Apprenticeship in Philosophy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Knibbe, Morgan. IDFA Q&A with Morgan Knibbe, November 28, 2014.

Lorraine, Tamsin. 2005. “Lines of Flight” in Deleuze Dictionary. Edited by Parr, Adrian. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Manning, Erin. 2013. Always More Than One * Individuation’s Dance. Durham: Duke University Press.

Massumi, Brian. 2012. “The Thinking-Feeling of What Happens.’ Inflexions, 1.1.

Massumi, Brian. 2014. What Animals can Teach us About Politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

McCosker, Anthony. 2015. ‘Drone Media: Unruly Systems, Radical Empiricism and Camera Consciousness” in Culture Machine, 16:1, pp 1-21.

Puar, Jasbir K. 2009. 'Prognosis time: Towards a geopolitics of affect, debility and capacity' in Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 19:2, pp. 161 - 172.

Rivette, Jacques. “On Abjection.” Translated by David Phelps and Jeremi Szaniawski. Jacques-Rivette.com. Accessed June 11, 2016. http://www.dvdbeaver.com/rivette/OK/abjection.html.

Shinkle, Eugene. 2015. “Drone Aesthetics” in Hyenas of the Battlefield, Machines in the Garden by Barnard, Lisa. London: GOST books.

Der Himmel über Berlin. 1987. Wenders, Wim.

Enter the Void. 2009. Noë, Gaspar.

Nuit et brouillard. 1955. Resnais, Alain.

Shoah. 1985. Lanzmann, Claude.

Son of Saul. 2015. Nemes, Lászlo.

Those Who Feel the Fire Burning. 2014. Knibbe, Morgan.

Notes

[1] A recent case in the Dutch media perfectly exemplifies how such responsibility is of great importance. On August 16th the newspaper The Volkskrant printed an article with the headline “Is Schiphol safe?” featuring a photo of road control by the army wherein an Islamic man is questioned (Volkskrant, 2016). A lot of commotion followed this publication as it was a clear example of framing, where the safety of the airport is directly linked to terrorism and to this ‘random’ Islamic man. Consequently, the main editor of the paper defended the picture saying it was nothing but a completely random photo and that if they chose to not use this they would fail to be objective. This example shows the irresponsibility which surfaces when not considering the propensity of the production-in-itself of an image to hide behind a preordained reality principle.[2] It is not surprising then that in the preface to the article of Serge Daney there is a commentary that Deleuze’s cinema books are in line with Jacques Rivette’s idea as developed in the seminal essay “On Abjection” (Daney 2004). Although the notion ‘image’ is not used, this is in fact what is discussed.

[3] Though a comparison would be reductive to both situations, one finds the impossibility of showing directly tied to films regarding the holocaust. An often repeated claim here is that any film that attempts to depict the happenings of this situation, as for instance Schindler’s List (1993), are but degenerative towards the actual occurrence, and thus ways other than showing must be elicited to approach the matter. One could think of the more poetic approach in Nuit et Brouillard (1955), the indirect approach in Shoah (1985), or more recently the persistent yet evasive approach in Son of Saul (2015).

[4] In A Thousand Plateaus Deleuze and Guattari already talk of this question, which is presumably the consequence of their own emphasis on the body-without-organs in Anti-Oedipus. This marks a shift to a problem internal to becoming, or rather, of the dangers of becoming, something most relevant today as Those Who shows us.

[5] As Michael Hardt writes: “In one sense, Deleuze’s being must be “determinate” in that being is necessary, qualified, singular, and actual. In the other sense, however, Deleuze’s being must be “indeterminate” in that being is contingent and creative” (Hardt, 2002: 127).

[6] Jasbir K. Puar says of affective politics that it “makes identity politics both possible and yet impossible” (Puar, 2009: 168).

Biography

Halbe Kuipers is a doctorate candidate at the Amsterdam School for Cultural Analysis. His project concerns a contemporary state of exhaustion as engendered by mediatised environments and what subjectivities it produces. Currently he is a visiting researcher at the Montréal based SenseLab, where is working on a project called care for the event considering care from an event-based perspective.