Emotional Democracy in Practice

Annoyance. – Usually it starts with annoyance, certainly when it is about politics. A feeling of anger that comes up because someone or something (in everyday life it may be the famous ‘perversity of the thing’) is bothering you. It comes along with the experience that something or someone is impairing you (in English you also can say in a more emotional way: ‘affecting’ you). There is an obstacle to the actions you are used to doing, and you are used to them because they express what you stand for. Annoyance (or hassle, or trouble) per se does not form a real problem, one that must be solved immediately or with a great deal of effort. It is like a fly buzzing around your head, crawling upon your skin, tickling your nose. You try to chase it off, once, twice, several times. And finally you either give up because you are too busy with other things, too tired, or absolutely serene (in the German sense of ‘gelassen’ that leaves everything the way it is). Or you get angry, really angry, and you try to catch that ‘damned dirty bastard’, to strike it dead, or even to shoot it. (A famous example for a funny way in between is offered by the opening sequence of Once Upon a Time in the West when one of the gunmen – performed by Jack Elam in his best ever unshaven and crumpled face – catches a fly in the barrel of his pistol, and then listens tenderly to its desperate buzzing.) Annoyance at that moment has transformed into anger. The slight feeling of anger has increased and has become real anger. Repetition has intensified a feeble emotion and has turned it into one that demands action. Anger cannot sit still. It has to start acting against the source of anger. If it doesn’t, if people go on stomaching the anger, they transform a psychological into a physical fact and sooner or later get sick.

Education policy. – In education policy things started that way in the middle of the 1990s. At that time so-called neoliberalism – an economical theory elaborated at the University of Chicago in the 1960s – had already established itself successfully on the political level. What had begun under the regime of General Pinochet in Chile and his ‘Chicago Boys’ in the 1970s, was taken over by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, the standard-bearer of conservatism in the 1980s, and they finally passed on the ideological banner in the 1990s to ambitious social-democrats like Tony Blair and a German chancellor called Gerhard Schröder (‘der Genosse der Bosse’, the comrade of the bosses). At that time neoliberalism – meanwhile a polemical term – started its attack on the universities in Europe. In 1999 the European Secretaries of Education signed the so-called Bologna Declaration that was intended to set up a unified European space of higher education. Essential, and meanwhile well-known elements, are two-stage degrees (BA and MA), the ECTS (European Credit Transfer System), and studies oriented towards employability.

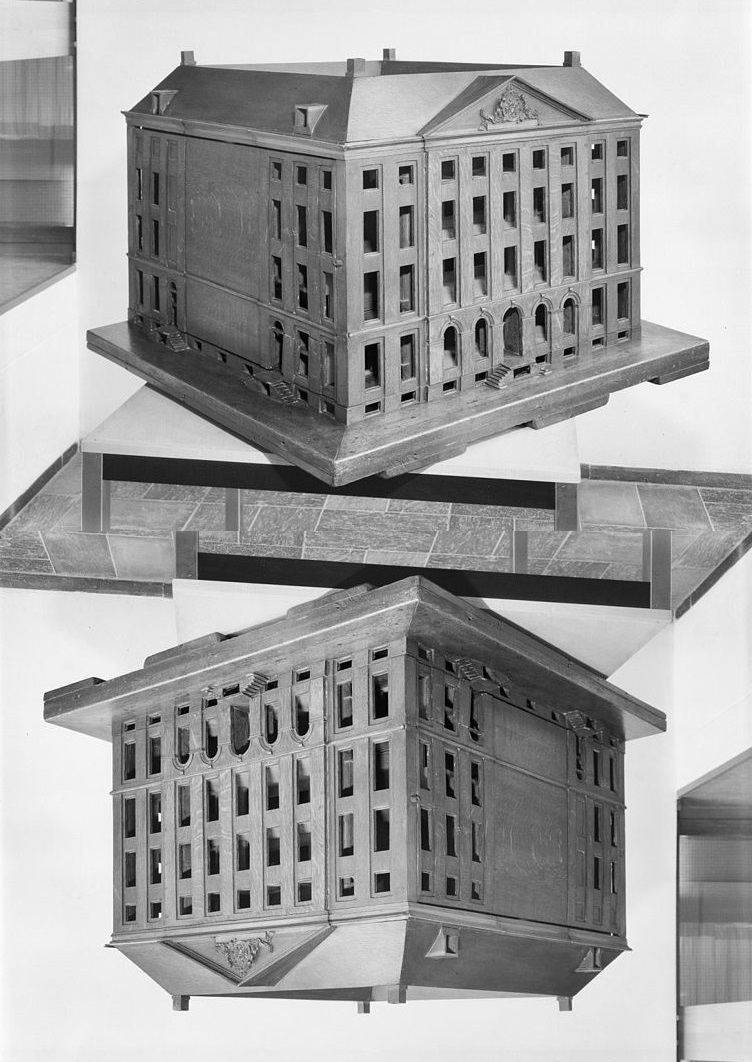

The University of Amsterdam. – Already some years earlier, in 1995, the Dutch Government decided to transfer the ownership of and responsibility for public real estate to universities (and schools, hospitals and other public organizations). That decision had huge consequences. When the Universiteit van Amsterdam (UvA), in 1998, came up with the ambitious plan to reorganize the university along four ‘centres’ or campuses, a first main step into a slowly increasing disaster was taken. Summing it up in a few numbers: In 2008 – the year of the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers – the UvA took out its first bullet loan of 55 million euros. For the first time in its history – established in 1632 during the famous Golden Age – this university became a net debtor. In 2011, total outstanding debt already had increased to 136 million euros, and it is expected to reach 400 million euros in 2018 (Engelen, etc. 2014: 1083).This caused a power shift in the management structures which becomes obvious by looking at the employees at the central administration building, the Maagdenhuis (House of Virgins, called that way because it once was an orphanage for catholic girls). There are 21 employees in the matter of Real Estate Management, 13 in the matter of Finance & Control, 8 in the matter of Strategy & Information, and finally 7 in the matter of Academic Affairs, which means teaching and research, thus the matter which was originally the core business of a university (when it did not yet think of itself in business terms).

This economic development brought about a drastic change of everyday work at the university. A change, however, that came in small steps which were difficult to immediately identify as pieces of a larger scheme: the redefinition and reshaping of academic life in terms of quantifiable economic efficiency, profitability and transparency. In the course of the protest movement the thinking pattern behind this change has received a new Dutch name: ‘rendementsdenken’ (rendement = return on investment). The process started out with baby steps, which were just annoying but – one by one – did not seem that dangerous. Yet the sum of those baby steps eventually led to a moral shock (Jasper 2011: 285-304). A huge number of students and teachers came to realize that the new management of the university had transformed academic life in such a way that it contradicts the core values which should guide academia.

Some examples. Teachers’ two main tasks – research and teaching – have been put under enormous pressure. As less research money is given directly to universities, academics have to spend an increasing amount of time – at the moment between 20 and 30 percent of their working hours – on writing research proposals submitted to research organizations. The time that remains for actual research and writing consequently decreases. But since the quality of research is measured increasingly by the quantity of publications, academics try to publish more while having less time to read the growing number of publications in their field of expertise. The distribution of research money on the basis of such a competitive system also produces the Matthew effect: those who have been successful once in receiving external research money, have increased chances to be successful a second and a third time. Those who have not been successful, have decreasing chances of ever being successful. As a consequence, the academic staff becomes more and more split into two groups: those who buy their way out for doing research and are highly valued by the management because of their work’s economic profitability, and those who do mostly teaching, many of them on precarious non-permanent contracts that enable the management to pursue a hire-and-fire policy depending on rising and falling student numbers.

As for teaching, the emphasis by both the Dutch education policy and the university management on ‘output numbers’ and ‘performance benchmarks’ has installed a system of quantification, control and bureaucratic transparency which makes it more and more difficult for teachers to put their energy into the highly creative, exciting, and inherently uncontrollable process of academic learning. The organization of teaching in the departments becomes dominated by the criterion of profitability: as many students as possible should get as many number of credit points as possible in order to receive a degree in as short a time as possible. These are the criteria that determine how much money faculties and departments receive from the Executive Board. Teachers and students are haunted by more and more tests according to more and more criteria (toetselementen). There are course manuals and examination files, feedback forms, standardization of working hours, ever more meetings to discuss these measures and ever more excel sheets to be filled in. The time that remains for preparing a seminar and talking to students diminishes and the thing that informs good teaching more than anything else – one’s own intellectual work – must be shifted to the evenings and weekends. A German colleague once mentioned that he feels like a jackass increasingly loaded by teaching, administration, committee, and fundraising tasks, and then sent into a race against the thoroughbred horses of elitist and often private universities like Harvard, Stanford, Oxford and Cambridge.

All these performance benchmarks (prestatieafspraken) and achievement provisions (studiesuccesmaatregelen) end up in streamlining the purpose of teaching; it gets more and more reduced to fact-checking. And since all these benchmarks and provisions are always imperfect and can be better, there is a correction and reform year after year. At the University of Amsterdam the collective limit of acceptance was exceeded for the first time when the Executive Board decided to go for a teaching system called 8-8-4. Within a semester-term a course had to be given in 8 weeks, followed by another one of the same length, and finally by a course of 4 weeks. Such a restructuring – established mainly for the reason that the UvA wanted to merge with the VU, the Vrije Universiteit of Amsterdam, where this teaching system was already established, a fusion which in the end failed – necessitates a huge amount of work and respective energy, above all if the people who have to do it are convinced that the whole operation is counterproductive. What can you teach to students of the Humanities in a course of 8, let alone 4 weeks? Forget close reading, the detailed analysis of arguments, and reflections on the premises of a text. Fact-feeding is the purpose of such a teaching system.

Rebellion. – The limit of acceptance was definitely exceeded when only two years after the 8-8-4 system was introduced, a plan for a new restructuring came up at the Faculty of Humanities. This time the reason was not a planned merger but a financial problem. Through some Friday afternoon emails sent by the Dean – emails, which sweetened our weekends in a cynical way – staff members were told that there is a shortage in the faculty budget. First, the administration gave us the number of some hundred thousand euros, but quickly it increased to 3 million, then 8 million, and finally 12 million euros. Nobody could tell exactly, and nobody could give convincing reasons for these shortages. The communication turned out to be disastrous.

The administration repeated that the Faculty of Humanities has to deal with a decrease in student numbers and thus with a decrease in available money, forcing the administration to lay off 100 teachers. After the protest had already spread, the central administration admitted that the costs for the ambitious real-estate plans of four campuses forces every faculty to deal – some more, some less – with drastic financial cuts, especially the Faculty of Humanities and the Faculty of Law. At the Humanities the administration started the process of ‘restructuring’ by a so-called ‘Profile 2016’, a ‘vision’ (it’s always very dangerous when admins talk of visions) to make the faculty enduring (duurzaam) and viable (levensvatbaar) by the means of an efficiency-battle (efficiencyslag).

This was the moment when the political emotions exploded. A process of continued top-down politics compressing the freedom of action of teachers and students, and executed with incompetence, both in planning as in communication, had finally reached its limit. And it was the language of emotions that put the matter in a nutshell. Suddenly a letter written by a professor addressed to the Dean and the Heads of the Departments was circulating among the members of the whole faculty. Explicitly it expressed a ‘shock’, and obviously it was a shock many people of the faculty shared. Active students appeared on stage under the name ‘Humanities Rally’, and when they organized a ‘Night of Protest’ everybody – including the Dean and a member of the Executive Board – could experience how all that frustration and anger which had been held back for a long time now broke loose. The well-established game of civilized retention did not work any longer. And, at least for a large group of people, the pervasive fear of speaking up was trumped by the moral outrage. This first moment of anger and rebellion later on culminated in the occupation of the Bungehuis, the administration building of the Faculty of Humanities, and – after it was evicted – the occupation of the Maagdenhuis, the administration building of the university.

Anger. – Anger is a respected emotion in the Western canon. It starts already with the first documented Western poetry and one of the most famous heroes of our culture. ‘Sing the anger of Achilles’, so are the first lines of Homer’s Iliad, thus honouring ‘anger’ or ‘rancour’ (the old Greek word is ménis) with being at the very onset of our culture. In philosophy, as well, anger is an acknowledged subject because in contrast to other aggressive affects – affects that foster activity or violence – like hatred, envy, or jealousy, it expresses itself in the language of morality. Anger is seen as an affect reacting to injustice. Thus there is ‘rightful’ and even ‘holy anger’. In contrast to hatred, anger knows a proportion, it isn’t excessive, and it doesn’t imply hostility. It usually comes up when you are convinced that someone offends against a norm that is very important to you. It is not clear whether such an emotion – like the non-aggressive emotion of shame – is constitutive for morality, but it clearly works as an indicator. The fact that a certain moral norm is important for a subject arises with the respective emotions: no emotions, no importance. But although a certain moral norm may not be important for a subject, it nevertheless may be seen as justified. Reading in the newspaper that someone has robbed a bank may not cause any emotion inside my chest, nevertheless I agree that the moral norm ‘Thou shalt not steal!’ in principle is right. Philosophically seen, we have to deal with the well-known difference between theoretical and practical validity. If someone doesn’t react to a violation – by himself or others – of moral norms by showing anger and indignation, or shame, we are allowed to assume that the respective norm doesn’t have validity in a practical sense for that person (Demmerling and Landwehr 2007: 287, 302; Lorde 1981: 7; Hessel 2010; Bromell 2013: 285-311).

Compensation and balance. – Anger and indignation, however, do not determine the process of protest. They stand for an emotion ‘that gets you in’; they do have a mobilizing power, and often are ‘at the core’ of the emotional and political dynamics of protest movements (Jasper 2014: 208-213). But at some point they need to be balanced and compensated by other emotions and moral values or even principles. If this works out well, the mechanism of compensation, or better, the art of balancing, in fact takes place. Since this balancing is a rule that can be learned only in practice, there is no meta-rule that could control its application. Immanuel Kant in that context speaks about ‘judgement’ (Urteilskraft), and Ludwig Wittgenstein also thought about this problem in an insisting way. Practical knowledge is habitualized knowledge, knowledge that has become a set habit; it is knowing how instead of knowing that. Watching, then, how often so-called negative emotions, like anger and shame, turn into positive ones, like joy, self-respect, and solidarity, is one of the really wonderful moments in a protest movement. You can watch it when people raise their voice for the first time as they take a stand; when a student speaks up and formulates her point perspectively; when the face of a colleague lights up and changes from frustration to enthusiasm after he has joined the protest.

Fear. – The power of these positive emotions – positive for the individual and the collective – is so strong exactly because the countervailing powers, of course (because an emotion, like fear, doesn’t vanish once and for all), remain present. One of them, maybe the strongest one, is fear. The protest at the University of Amsterdam was going on already for some months. Nevertheless the buzzword ‘culture of fear’ hung hard-bitten over all assemblies. It was obvious that many colleagues did not dare to speak their mind as they were afraid of losing their job. The ‘silent majority’ in such a case is in fact a ‘silenced majority’.

Shame. – Another emotional countervailing power is shame. The British writer Marina Warner has put into words how the current university management of the UK – similar to, and even worse than the one in the Netherlands – works with that emotion. The managers count on shame – in others, of course, not in themselves (Warner 2015). Shame means the excruciating fear of being worthless because one does not fulfil a (moral or social) norm. It most commonly appears in the form of an inner voice which has two messages and smoothly switches back from one to the other. Either it says: ‘You are not good enough!’, or it says: ‘Who do you think you are?’ When people struggle to keep up with the output expectations in everything they do, they are quickly paralyzed by the thought: ‘You are not good enough!’ If they try to break out of it, stick true to what they passionately believe in, the ‘Who do you think you are?’ message will immediately step in to make them feel miserable and apathetic again.[i]

Respect. – Among the emotions and values that compensate and balance anger, fear, and shame, respect turns out to be a very important one. In philosophy it is, once again, controversial whether respect is an emotion at all. As an acute feeling respect has to be something that befalls us, and thus something that cannot be controlled by our will and moral intention. As an habitualized attitude, on the contrary, it is deeply moral but detached from emotion. Kant’s respect of human beings as purpose in themselves delivers the best example for this. There is a third possibility in between, and this is respect as an emotional disposition because one can have the disposition towards respect for somebody without having the respective emotion at every encounter, and without aiming respect in the Kantian sense at everybody. And, finally, there is another possibility called ‘civility’. It is within this context that Kant’s conception of respect as ‘intelligible’, as a feeling brought about by reason, gets some visual evidence.

Respect, civility, and self-care. – During the many days (and nights) of protest around the Maagdenhuis the students have demonstrated what being respectful of others means. The task of chairing debates, spontaneous meetings, and General Assemblies bringing together teachers and students was always delegated to a student. Although there were so many different people, i.e. incorporated experiences, present in the room, and although there was no guarantee at all that there would be an agreement in the end (though urgently needed), the crowd managed every time. When it is about the advantages of democracy, John Dewey talks about ‘pooled intelligence’ (1937: 457-67)[ii]. Here, at the Maagdenhuis, one could see it at work. The amazing result of consensus was not only brought about by people who are bound together by a shared political aim, and therefore have an instrumental reason for finding consensus. It was also the result of people who honour the emotional challenge such a situation means for everyone involved. It simply was touching to see students regularly taking the responsibility of reminding everyone in a soft voice that they should stick to the rules of discussion. They knew how quickly a debate can derail because human passions are running amok instead of being channelled into a productive form. They understood that we have to protect ourselves by carefully fostering our civility. They understood that people have to enact what they are striving for in order to achieve it: starting any discussion and any action with a genuine respect for everyone involved, including for ourselves. Thus there is also a kind of self-respect at stake here, a kind which is intermingled with self-care.

The elements of moral respect, civility, and self-care form a constellation that allows to zoom in on Kant’s very specific concept of respect as an intelligible feeling. In Kant such a feeling is effected by ‘pure’ (moral) reason, and therefore it implies that it is universal; directed towards everyone. A weaker reformulation in the sense of civility does not imply that such an intelligible feeling is effected purely by moral reason but that it is tied up with reason. Such a reformulation accepts our conditio humana, the fact that we make mistakes, but at the same time remains aware of something which is bigger than us; which is in a certain sense sublime. (And that is the reason why Kant connects respect very closely with the sublime). Civility is an habitualized attitude of respect which is neither restricted to single persons and acute feelings, nor extended to all persons in a universal and de-emotionalized way.[iii]

In the end respect as an acute feeling comes up, as well. Watching a situation when diverse emotions are channelled in a productive way by a diverse crowd; that is to say, when emotions are balanced and compensated by other emotions and moral values, cannot but lead to a feeling of respect for everyone involved, respect now in the French sense of ‘Chapeau!’ or in the German sense of ‘Alle Achtung!’ Respect here is directed towards an achievement which is not necessarily a moral one. The achievement is: handling a collective situation with moral respect and sensitivity, i.e. with civility. If, on top of that, wit and humour are added, the thing is not only impressive but positively enchanting. As a teacher you may ask yourself what you could teach these students anyway. Some expertise, certainly. But they do have already the skill for one of the most important things in life.

Theoretical backing. – If we want to have a theoretical backing for those observations, we can easily refer to Martha Nussbaum’s recent work. She has published widely on the role of emotions in moral philosophy. In her voluminous book Political Emotions. Why Love Matters for Justice she offers a broad discussion about the connection between politics and emotions, especially between politics and love. Somewhat too airily Nussbaum likes to make clear and oppositional distinctions between so-to-speak good and bad emotions. Thus she calls emotions like fear, envy, and shame ‘compassion’s enemies’, and she defines compassion as ‘a painful emotion directed at the serious suffering of another creature’, thus as an emotion that links us to others, be it humans or animals (Nussbaum 2013: 142, 314).[iv] In the case of fear this means that such a ‘narrowing emotion’ – an emotion ‘with a very narrow frame, initially at least: one’s own body, and perhaps by extension, one’s life’ – needs to be combined with ‘general concern’ or, in the language of the 18th century, with ‘sympathy’. Such a combination then leads to a ‘tempering’ of fear. One of the examples Nussbaum refers to is Roosevelt’s First Inaugural Address from 1933, thus a political speech, with the most famous line: ‘the only thing we have to fear is fear itself – nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts …’ (Nussbaum 2013: 320, 326). In the case of envy, similarly, as an ‘antidote’ we need ‘a sense of a common fate, and a friendship that draws the advantaged and less advantaged into a single group, with a common task before it.’ Examples are delivered again by a Roosevelt speech, by Gandhi’s strategy to convince elites to adopt a simple lifestyle, and by building New York’s Central Park as a ‘People’s Park’. But in the case of envy it is evident as well that ‘much will have to be done by laws and institutions that make basic entitlements secure for all, and by educational and economic systems that make people feel they have constructive alternatives’ (Nussbaum 2013: 344, 345). Thus the political role and the public cultivation of emotions – essentially articulated by artists and poets as well – has to be supported by political, economic, social, and cultural institutions. And besides this it also has to be limited by the normative goals of a liberal society, among them the very well known goals of equal respect for persons and a commitment to equal liberties of speech, association, and conscience. The framework of liberalism remains sound in Nussbaum. The ‘challenge’ her new book takes up is to offer more than liberalism – the liberalism of Locke, Kant, and Rawls, not so much the version presented by Mill – without becoming illiberal and even dictatorial in the manner, for example, of Rousseau (Nussbaum 2013: 5).[v] It is that challenge, not the suggested solution, that makes Nussbaum’s book important.

Aesthetic transformation. – If we ask ourselves on a general theoretical level how to deal with emotions in politics, that is in the public arena of ethical conflicts, that is in an arena where conflicts about how one should live are discussed, negotiated, and – sometimes violently – solved, there are at least two answers. We were talking already about the first one under the heading ‘compensation’ and ‘balance’. The second answer popped up when we were talking about ‘the art’ of balancing and the ‘sublime’ aspect of respect. Whereas the first way of dealing with emotions in politics aims at a practical system of compensation and balance (it is a practical one because in the end you have to learn it by doing it), the second way aims at a transformation of emotions. And art, or in a broader sense, aesthetic experience, is an ideal means for this.

Like every protest movement, the protest around the Maagdenhuis made use of aesthetic forms of expression. Most prominently, of course, there is the use of language known from its Greek beginnings as rhetoric, in addition there is the use of images, and finally of body performance. When the ‘Night of Protest’, the first public event, took place at the Humanities, and one of the young active students gave a short speech finishing with: ‘I am Julia. I am human. I am Humanities’, the protest had found its first slogan. Posters quickly followed, each of them playing with the slogan. On one of them Van Gogh is looking at us in a famous self-portrait and gives us the message: ‘I am human. THINK. Humanities Amsterdam’. People changed the logo of the University of Amsterdam. The three St. Andrew’s crosses – the one in the middle enclosed by a ‘u’ for ‘university’ – in a vertical line were put in a horizontal line, thus symbolizing the anti-hierarchical, democratic, and – last but not least – emotional constitution of the new university (alluding to the three xxx symbolizing hugs at the end of a mail). With historical pathos and irony a protesting staff member offered grand comparisons on twitter between the events in Amsterdam in 2015 and in Paris in 1789: ‘We will stay here until we have a new Constitution’ was the famous oath at the Jeu de Paume, and it became an expression of the will to stay of the occupiers and their supporters in the Maagdenhuis combining a photograph of the General Assembly on the night of the occupation with a copy of the famous drawing by Jacques-Louis David.

Twitter is generally an important technical medium in that context. Tweets have to be short, and mostly they are meant to spread news, sometimes gossip, and to comment on current events, sometimes in hate-speech. (In general we should not deny that next to the regulars’ table and the stand in a football stadium, twitter is a legitimate form of unfiltered expression of opinion in a modern society.) But some of the tweets are formulated very finely, that is to say that they comment and insinuate with the means of rhetoric. But also classical posters can do the trick. After the Executive Board (College van Bestuur, CvB) had finally formulated a letter including ten points for further, and now constructive discussion, somebody hung a poster in the Maagdenhuis that was also tweeted. It showed a drawing of an astronaut with newspaper articles about the University of Amsterdam in the background. It stated ‘The #CvB proposal seems like a huge step for them, but it’s a small step for humanity #houstonwestillhaveaproblem’ alluding to the famous quotation of the first man on the moon in 1969. (‘That’s one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind.’) And since many people within the protest movement were still very sceptic about the real or good intentions of the CvB, they (intended to) remind them of this scepticism by referring to a song by Sting that itself plays with a slogan of the surveillance society (‘Big Brother is watching you!’) integrating it into a love song that sounds gentle but is sinister: ‘#CvB Every word you say, every game you play, we’ll be watching you.’ Of course, a classical rally makes equal use of aesthetic elements, from slogans for the crowd and banners via music – indispensible for many years: drums – and noise – indispensible for many years as well: whistles – to costumes. The rally that took place after the Maagdenhuis was evicted had an ironic aesthetic touch by the mere fact that many people – both staff members and students – decided to dress up nicely and even respectably by wearing a fashionable robe, a suit with tie (or a tie without a suit), or a toga (if they were professors). As always when students who usually do not look like bank employees do things that do not seem decent – like occupying a building –, a part of the published public opinion let their resentments run wild and bad-mouthed the students as long-haired, dirty, left-wing, lazy-bones. Since public opinion is massively influenced by images as well, the students and the larger protest movement simply can prove such resentment wrong by making it look silly. (Maybe this is the only realistic way to disprove a resentment.) So they dress up and deliver nice pictures to tv stations and the press.

Aesthetics helps us to take bad things seriously and not seriously at the same time.[vi] It can do so – but this is a thesis that needs to be defended in more detail – because it has a transformative power. The structural reason for this seems to be its status in between well-established oppositional relationships like those of reason (the realm of argumentation) and emotions, or the universal and the particular, or the abstract and the concrete. In his Critique of Judgment Kant has specified this status in a positive way by ascribing to aesthetics the capacity of exemplary presentation. A work of art, or a corresponding aesthetic experience, does not present itself as an abstract theory with a universal validity claim. But it is not a mere singular object or experience either. Instead it presents something in an exemplary manner. It is able to intensify the experience of a situation by concentrating it in a particular constellation of (visual, verbal, and auditive) signs. Thus, if we want to know what anger ‘is’, that is what this emotion actually means, including its unfolding nuances, we have to read Homer’s description of Achilles, or the Old Testament, or Kleist’s Michael Kohlhaas. If we want to know what hatred is and love, envy and practical solidarity, we have to read novels, poems, listen to operas, and watch movies. Works of art baptise our emotions. Of course, we can look up a definition of anger, hatred, love, or solidarity in a dictionary, but this only provides us with a description that remains detached from our own experiences. A novel, a play, an opera, a movie does not provide us with a definition, but the way it presents a story lends that story a validity that goes beyond the particular case. This is also the reason why aesthetic ways of expression can elevate the emotions that are part of it above a mere private sphere. It is an individual who speaks up for something in public. But if she does it – aesthetically – right, she expresses a public opinion.

The power of exemplification, finally, is also the reason why aesthetic ways of expression can be very helpful in building up positive motivations during a political struggle. Once the members of a protest movement – in general a small one – think of themselves as fighting the whole world, in philosophical terms fighting society as a negative totality, because (almost) nobody is able to understand them, it needs a lot of humour, calmness, or intellectual narcissism not to get frustrated. In that context political action either opts for violence, or takes a back seat by sending a message in a bottle. Theodor W. Adorno wanted to send such a message. But his colleague Hanns Eisler rightly remarked that he already knew how the message would read, namely ‘I feel so lousy.’[vii] Adorno thought of art as being such a message. But the actions around the Maagdenhuis in Amsterdam – once again – tell another story, one that is closer to another companion of Adorno, namely Herbert Marcuse. It is essentially by aesthetic experiences that – listening to the Rolling Stones – the ‘poor boys’ and girls and queer beings who are ‘fighting in the street’ keep on rollin’.

Referenties

Bromell, N. (2013) ‘Democratic Indignation: Black American Thought and the Politics of Dignity.’ Political Theory 41 (2): 285-311.Brown, B. (2012) Daring Greatly. New York: Gotham Books.

Demmerling, C and H. Landwehr (2007) Philosophie der Gefühle. Von Achtung bis Zorn. Stuttgart and Weimar: J. B. Metzler.

Dewey, J. (1937) ‘Democracy and Educational Administration.’ School and Society 45: 457-67.

Engelen, E, R. Fernandez and R. Hendrikse (2014) ‘How finance penetrates its other: a cautionary tale of the financialization of a Dutch university.’ Antipode. 46, 4:1072–1091.

Hessel, S. (2010) ‘Indignez-Vous!’ Montpellier: Indigène.

Jasper, J. M . (2014) ‘Constructing Indignation: Anger Dynamics in Protest Movements.’ Emotion Review 6, 3: 208-213.

Jasper, J. M. (2011) ‘Emotions and Social Movements: Twenty Years of Theory and Research.’ Annual Review of Sociology, 37: 285-304.

Lorde, A. (1981) ‘The Uses of Anger.’ Women’s Studies Quarterly 9, 3: 278-285.

Nussbaum, M. (2001) Upheavals of Thought: the Intelligence of Emotions. (part II) Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nussbaum, M. (2013) Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Rahden, T. (2011) ‘Clumsy Democrats: Moral Passions in the Federal Republic.’ German History 29, 3: 485-504.

Rosenthal, I. (2014) ‘Aggression and Play in the Face of Adversity: A Psychoanalytic Reading of Democratic Resilience.’ Political Theory 42 4:1-24.

Scholz, Natalie. (2015) ‘On the Wonders of Solidarity @Maagdenhuis.’ http://rethinkuva.org/blog/2015/03/21/on-the-wonders-of-solidarity-maagdenhuis/

Tangney, J.P. and R. L. Dearing (2002) Shame and Guilt. New York: The Guilford Press.

Warner, M. (2015) ‘Learning My Lesson.’ In: London Review of Books 19, March 2015.

Weeks, T. R. (trnsl.) (1986) ‘The Utopian Motif in Suspension: A Conversation with Leo Löwenthal.’ New German Critique 38: 437-469.

Noten

[i] Cf. Natalie Scholz, ‘On the Wonders of Solidarity @Maagdenhuis’, http://rethinkuva.org/blog/2015/03/21/on-the-wonders-of-solidarity-maagdenhuis/, with an implicit reference to Daring Greatly (Brown 2012). See on shame also Shame and Guilt (Tangney and Dearing 2002).[ii] ‘While what we call intelligence be distributed in unequal amounts, it is the democratic faith that it is sufficiently general so that each individual has something to contributwhose value can be assessed only as it enters into the final pooled intelligence constituted by the contributions of all’ (Dewey 1937: 457-67).

[iii] Loc. cit., p. 55, on Kant see pp. 42 (Demmerling and Landwehr 2007); from a historical perspective: Rahden 2011: 485-504.

[iv] For her analysis of compassion see also her book Upheavals of Thought: the Intelligence of Emotions, Cambridge University Press 2001, pp. 297-454 (part II).

[v] As to Rawls, Nussbaum emphasizes that he explicitly leaves a space for, as he calls it, a „reasonable moral psychology’, and that her book „aims to fill that space’ in a way „that differs from Rawls’s in philosophical detail, but not in underlying spirit’ (p. 9).

[vi] In this sense it works similarly to Donald Winnicott’s psychological concept of play (Rosenthal 2014: 1-24).

[vii] W. Martin Lüdke: ‘Das utopische Motiv ist eingeklammert: Gespräch mit dem Literatursoziologen Leo Löwenthal’, in: Frankfurter Rundschau, 17.05.1980, published in English in ‘The Utopian Motif in Suspension: A Conversation with Leo Löwenthal’ (Weeks 1986).

Biografie

Josef Früchtl (http://home.medewerker.uva.nl/j.fruchtl) is professor of philosophy with a focus on philosophy of art and culture (Critical Cultural Theory) at the University of Amsterdam (UvA). He is publishing in the field of aesthetics (with a focus on aesthetics and ethics as well as aesthetics and politics), Critical Theory, theory of Modernity, and philosophy of film. His recent publication is Vertrauen in die Welt. Eine Philosophie des Films (München: Fink 2013), translated as Trust in the World. A Philosophy of Film (New York & London: Routledge 2018).

Natalie Scholz is Assistant Professor of Modern and Contemporary History at the University of Am-sterdam. She works on the cultural history of the political in modern Europe (France and Germany) with a focus on symbolic representations, popular imaginations and their affective dimensions. In her book Die imaginierte Restauration (Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft 2006) she interpreted popular imaginations of the French Restoration Monarchy as cultural expressions of political feelings framed in a melodramatic mode. Currently she is working on a book project about the political meanings of every-day objects in postwar West Germany.