What Should Democracy Mean in the University

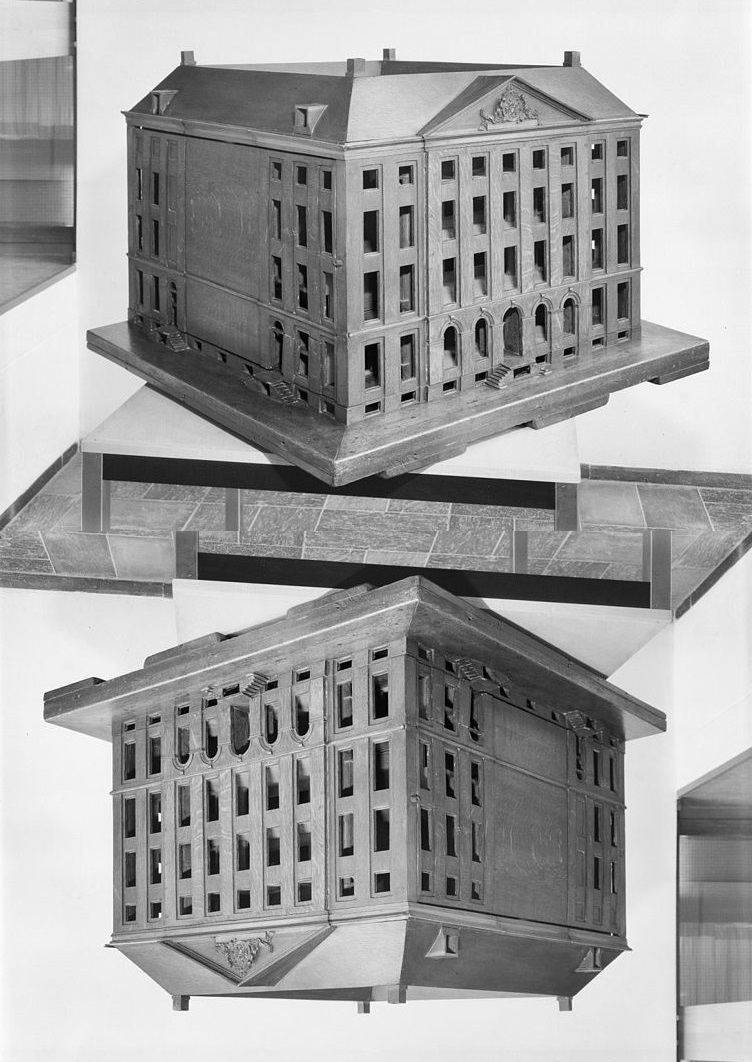

The 2015 occupation, or, if one will, reappropriation, of university space in Amsterdam that started a national movement for a ‘New University’ in the Netherlands and that possibly (witness the LSE, the UAL, King’s College and others) inspired others internationally,[1] constituted a political event. It constituted a political event because, for some time, it forced a breach in the normalized but utterly empty discourse of excellence that has conquered universities in the last decades. Suddenly it became possible to say that too much emphasis had been put on efficiency (rendement), that universities had been run on the basis of an extremely thin legitimation that in fact amounted to a neoliberal ideology, and that many universities had undergone a process of financialization that had contributed to the promotion of efficiency and return-on-investment ideas and practices to the primary if not sole goal of the university. Suddenly also, administrators at the University of Amsterdam admitted that they agreed with many of the things put forward by the students, and they were ready to make concessions of various nature. However, administrators mostly promised to continue ‘discussion’ and ‘debate’, and the initial refusal by the students to engage in sublimating, normalizing and consensus-seeking discussion greatly enhanced the political space that had been opened. Suddenly, university politics did not mean bargaining. Suddenly it was about principled positions, and holding ground – literally, by occupying the space of first the Bungehuis and later the Maagdenhuis (seat of the administrative board of the University of Amsterdam).

And then came the faculty. Picking up on some of the demands of the students for an internal democratization of the university, ‘democratization’ became the main focal point of what was called ‘Rethink University of Amsterdam’ – a community of faculty from different departments and faculties. The internal democratization that became the main object of struggle for Rethink UvA, and for many other ‘Rethink’ communities around the Netherlands, entailed demands for elected administrators, participation in all crucial decision-making, and that the prerogative of such decision-making should be solely for faculty with input from students. And that, as far as I am concerned, closed down the political space forced open by the occupation of, primarily, the Maagdenhuis. This political space got filled with increasingly intricate procedural proposals. It turned out that what it was all really about was the governance model. The conception of democracy Rethink UvA espoused – and still holds onto – is a type of participatory democracy or, perhaps better, direct democracy, which was also in practice among the students that occupied the Maagdenhuis. It entailed a set of procedures known amongst others from Occupy Wall Street, and at its core is a model of democracy that is radically nonrepresentational but also radically consensus oriented. Inspired by Occupy Wall Street, its model was not that of deliberative democracy (which assumes consensus about the reasonable limits of legitimate deliberation), but direct democracy, which hinges entirely, for instance in the format of the ‘general assembly’, on a form of immediate consensus.

The limits of internal democratization

With respect to these demands for internal democratization, I should like to make four points:

- First a rather practical point. Internal democratization along the lines suggested during the Maagdenhuis occupation is likely to lead to the articulation of special interests and of the greatest interests, and this will not necessarily be favourable for the humanities. This touches on the larger issue of representation or spokespersonship. For whom and on behalf of whom at their universities do ‘Rethink’ movements speak? Large faculties or departments such as economics, business administration and law, let alone the organizationally anomalous medical faculties, have shown (and are likely to show) very little interest in supporting the demands of protesters. Should democratization lead to referenda, elected officials and the like, this would most likely not end up in the interests of the current protesters. We have to face the fact that many – students and faculty – simply have no problems with the way things are going in Dutch universities. This became explicitly apparent in the show of support for the board of administrators at the University of Amsterdam in April 2015, but it also speaks from the silence of most of the faculty at Dutch universities. It remains a difficult task to convince them that they have it wrong without treating them as the docile clients of an ideological state apparatus (treating them thus is of course an option as well).

- Relatedly, the heavy focus on internal democratization smacks of a certain conservatism and an effort to safeguard academic (including professorial) privileges. These privileges mainly have to do with the fact that many in contemporary Dutch academia are publicly funded to perform in a context defined almost completely by internally defined goals, without any practical and consequential concerns of the role of the university in democracy at large. This not only becomes apparent due to the fact that the protests have so far lacked a convincing conception of the public uses of the university (I have made a modest proposal in Schinkel 2015), since – at best – 19th century conceptions such as Bildung have dominated the accounts of the protesters alongside what are often clichéd accounts of neoliberalism, according to which ‘the market takes over from the state’. A more interesting account of neoliberalism, also applied to academia, is given by Wendy Brown in her recent book Undoing the Demos. Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution, where she argues (based on Foucault’s lectures on biopolitics) that neoliberalism constitutes a specific rationale – based on market principles – that is extended to non-market domains. And yet interestingly, a similar wish to preserve what exists becomes apparent in her book. According to Brown, liberal arts education has been crucial for democracy in the sense that it helped create an informed, educated public. This liberal arts type of education she then deems crucial to democracy at large: ‘a liberal arts education available to the many is essential to any modern democracy we could value (…) to preserve the kind of education that nourishes democratic culture and enables democratic rule, we require the knowledge that only a liberal arts education can provide’ (Brown 2015: 200). While I am overall sympathetic to Brown’s argument in Undoing the Demos, this type of argument about the democratic relevance of liberal arts education is simply unacceptable. Is she saying European countries, without a liberal arts tradition, have not been proper democracies? She might be right, but certainly not for the reason of not having liberal arts curricula. One could qualify her points on democracy and liberal arts as a form of US-centrism that comes with occupying a hegemonic position – which it certainly is – but beyond that one could say that here, too, a conservatism becomes apparent. In the US, one argues that liberal arts should be retained because it is crucial for democracy. In Europe, the exact opposite is argued: no liberal arts, but disciplinary education, because of its relevance for dmocracy. In both cases, an argument is made to preserve what exists. This idea of conservatism is also warranted in the case of the University of Amsterdam because up until the moment budget cuts came, no faculty protests appeared (exceptions were exactly that). For decades, the legitimation of being publicly funded at universities has been neglected precisely because the money kept coming – even though students have become increasingly indebted for more than 10 years now. But once faculty positions are at stake, hell is raised.

- The prevailing conception of ‘democracy’ in the protests is heavily focused on consensus, and it appears based on a neglect of the fundamentally violent dimension of any form of governing. In some respects, it bears remarkable resemblance to a D66-type of conception (D66 is a Dutch political party comparable to the UK’s LibDems), especially when it emphasizes political participation through referenda and elected officials. The history of the use of such instruments does not warrant the idea of revolutionary change (I will have a bit more to say on this in the next section). More importantly, though, the problem here lies in the effort towards ‘participation’ (in politics known as the half-hearted wish to ‘bridge the gap between citizens and politics’) and a form of consensus. Over against consensus and direct participation I would emphasize contestation and distance. Contestation actually allows one to formulate one’s ideals without the burden of sorting out complex practicalities. It allows one to retain a critical stance vis-à-vis administrators, and to have the possibility to vigorously contest what they do. Direct democracy, on the other hand, draws everybody into the process of decision-making, thereby losing the possibility of a critical stance. The very practical form of assembly used in the protests, with regular ‘temperature checks’ and waving hands, is utterly unconducive to articulating dissenting opinions, which means it not only undermines the democratic need to facilitate minorities, but it also digresses towards a conservative and inflexible position, with limited possibilities of openness to new ideas. The only circumstances in which drawing everybody into decision-making and the loss of a critical position would not matter constitute a situation in which direct democracy did not entail some form of, ultimately, violence, i.e., some form of decision-making that of necessity compromises and represses the wants, needs and hopes of some. Such a conception of the political at large is, quite simply, extremely dangerous because it can only accept minority positions as depoliticized procedural outcomes. And so even in the much more inconsequential context of university politics (all pathos aside), I would strongly argue against it.

- Finally, participation in all internal decision-making is characterized by a certain professional arrogance that is part of the larger, extremely simplified, frame of ‘professional versus manager’ that involves slogans like ‘the managers have taken over!’ Just because we as faculty work in universities does not mean we are best qualified to organize them. A similar mistake would be made by a patient telling the doctor she knows all about medicine, because she has a body. In some bygone age, perhaps, scholars could lay claim to a wide variety of combined expertise (Newton, for instance, was governor of the Mint), but in our time a profound and arrogant neglect of the complexities of organization and administration entails the suggestion that scholars might do it on the side. Now, crucially, by this I do not mean to suggest that existing administrators have done a fine job. On the contrary! And I’m very glad with the possibility of contesting what they have done, I’m just not so sure that such contestation is best served by forms of participation (inspraak) informed by either direct democracy or deliberative democracy. In fact, many of the griefs of faculty have to do with the fact that, in practice, they have become both professional and manager, which frustrates many because they feel their managerial duties keep them from their primary tasks, which for them are research and teaching (in that order). I agree that such a conflation of professionalism and managerialism is often unwanted, but I would insist that professionals need to reconsider their claims in knowing best how to run a university. Precisely when professionals are good at what they do, and do it indeed as a ‘profession’ in the Weberian sense of a Beruf, they tend (like managers) to be otherwise partial, biased and generally unfit for making decisions in the collective interest that, at times, will necessarily negatively impact their – in practice – narrowly conceived interests. Finally, I do not favour direct democracy in universities because, from the intellectual point of view of a scholarly professional, the everyday tasks of decision-making, organizing and administering are downright boring. So thanks but no thanks.

All this does not mean administrators should be unresponsive to the claims by faculty, or that universities should not first and foremost operate out of a shared substantial conception, formulated by faculty, of what universities are for. Quite the contrary, but I believe these claims and conceptions are better formulated and served when formulated at a distance from day-to-day administration.

Beyond academic capitalism and academic conservatism

Against my expose in the previous section, one might say that an internal democratization of the university is the precondition for the democratic, critical and emancipatory contributions universities make to the world at large – a goal to which I wholeheartedly subscribe. But that would mean that universities were not, on the whole, conservative institutions. And all the evidence points precisely in this direction. The impetus to protest at the time at which it occurred was always to a considerable degree conservative at the University of Amsterdam. A unique collusion of events gave rise to a movement that drew together important parts of the university. First there was the position of the humanities, threatened by budget cuts. Second, there was the top-down move towards a merger of the science faculties of the University of Amsterdam and the VU University (also in Amsterdam), which occurred mostly out of reasons exemplifying academic capitalism (efficiency, rankings etc.) and against the wishes of the majority of the students and the science faculty at the University of Amsterdam. In both cases, then, maintenance of the status quo was the preferred option by protesters. That this is typical of universities has been argued forcefully by Clark Kerr, president of the University of California form 1958 until 1967. In a later essay added to his book The Uses of the University, Kerr discusses the student protests of the 1960s. In those protests, he had an important but contested role as university administrator. Students hated him, and at one point he was called a ‘fascist’, but at the same time the FBI blacklisted him as a subversive liberal and he was fired under such pretenses by then governor of California Ronald Reagan. Looking back on the demands for what he calls ‘participatory democracy’, Kerr notes the conservatism these demands exemplified, and I quote him here because of the clarity of his account and the relevance it has in today’s context, even if what he calls participatory democracy may not be exactly what is proposed today:

‘It is ironic that participatory democracy, with its emphasis that all the ‘people’ should be consulted and all groups have a veto, which was supposed to result in more radical decisions, in more speedy and more responsive actions, has meant, instead, more veto groups, less action, more commitment to the status quo – the status quo is the only solution that cannot be vetoed.’ (Kerr 2001: 134)

Kerr’s larger point, however, is that calls for internal democratization were in the end merely another way in which a general conservatism typical of universities played out in the 1960s. Overall, he argues, universities are very, very slow to change, and this is largely due to the conservatism of faculty members with respect to their own positions. Historically, universities are indeed remarkably stable and longstanding institutions. As Kerr notes:

‘About eighty-five institutions in the Western world established since 1520 still exist in recognizable forms, with similar functions and with unbroken histories, including the Catholic church, the Parliaments of the Isle of Man, of Iceland, and of Great Britain, several Swiss cantons, and seventy universities.’ (Kerr 2001: 115)

As Guldi and Armitage have recently argued, this goes for the non-western world as well: ‘Historically, universities have been among the most resilient, enduring, and long-lasting institutions humans have created. Nalanda University in Bihar, India, was founded over 1500 years ago as a Buddhist institution and is now being revived again as a seat of learning’ (Guldi & Armitage 2014: 5). And so, as Clark Kerr concludes, ‘looked at from within, universities have changed enormously in their emphases on their several functions and in their guiding spirits, but looked at from without and comparatively, they are among the least changed of institutions’ (Kerr 2001: 115). Indeed, what Thomas Jefferson wrote about church and state in his plea for the founding of the University of Virginia seems to apply just as much to universities:

‘the tenants of which, finding themselves but too well in their present position, oppose all advances which might unmask their usurpations, and monopolies of honors, wealth and power, and fear every change, as endangering the comforts they now hold.’ (Jefferson 1818: 12)

I would argue that current protests exemplify a longstanding conservatism and that, while the protests are just and admirable, this conservatism works counter to the establishment of really positive change. Many protesters, for instance, make it seem as if the contingent, historically evolved set of disciplines taught at universities today is God-given, written in stone, and that not a single thing might be changed in them. Of course, as protesters have rightly argued, any change should be backed up by a good story. This can’t be emphasized enough: policy-makers and politicians in The Hague have no tolerance for the type of arguments currently put forward. And for this reason alone, even though I can at some level agree with very many of these arguments, I believe a more seductive argument is needed. So let me posit here, for the sake of argument, that what is shared by protesters and administrators is that they – we in general – lack such a story beyond the types of conservatism discussed above. Even the complaints of protesters have remained largely unchanged. In 1967 Theodore Roszak could write:

‘And what are the imperatives our students would find inscribed upon their teachers’ lives? ‘Secure the grant!’ ‘Update the bibliography!’ ‘Publish or perish!’ The academic life may be busy and anxious, but it is the business and anxiety of careerist competition that fills it.’ (Roszak 1967: 12)

What we have, then, is on the one hand an academic capitalism that is – still – rightly contested, but unfortunately, it is contested by an academic conservatism that seeks administrative participation as a way to secure privileges. Unfortunately, for those implementing ever new forms of academic capitalism (let’s be clear on the fact that this happens, and on the detrimental effects it has), academic conservatism becomes a tool. Larry Summers, for instance, former President of Harvard and former US Treasury Secretary (as such responsible for the repeal of the Glass-Steagal Act by adopting the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act, paving the way for the credit crunch), said that universities ‘have the characteristics of a workers’ co-op. They expand slowly, they are not especially focused on those they serve, and they are run for the comfort of the faculty’ (The Economist 2015: 16). The sad thing is that he is half right. So far, what has mainly been marshalled against academic capitalism is an academic conservatism. What a sorry state this is for those who lack affiliation with either position!

I’m aware that my use of ‘conservatism’ is somewhat provocative here, and it is conceptually limited to the colloquial sense of wishing to preserve what exists (and so it has nothing per se to do with political conservatism). I use the concept precisely to point out the fact that, in nearly all the protests I witnessed firsthand, the past served as the reference point for the desired situation. Some golden age of the university was often assumed to have existed, and it was vaguely situated in the 19th or the 20th century – two centuries in which universities in both Europe and the US have been almost incomparably different. As noted above, the Dutch embrace of disciplinary education and the protests in Amsterdam against a ‘watered down’ interdisciplinary bachelor in the humanities are in exact accordance with the opposite claim for liberal arts voiced by Wendy Brown. What may well become visible in these discussions and protests is the truly very limited capacity of people to analyze the situation and context in which they have been raised and are enmeshed in, with all the interests such enmeshment brings with it. When I speak of conservatism here, it is intended to provoke three things: 1) a better historical awareness of the situation deemed desirable; 2) a rhetorically more convincing argument, since arguments-from-loss appear as resentment and have no political traction; 3) a conception of the university that is much less focused on internal democracy, and (as Wendy Brown does convincingly albeit with little specificity) much more geared towards specifying the university’s role in democracy at large.

The public tasks of the university

If we are to take seriously the problems that the protesters address – ‘academic capitalism’ is one way of phrasing these problems – but move beyond such conservative responses, we need to renew our understanding of the public tasks of the university. We have in common with administrators the neglect of those tasks when things went well. When trying to formulate them now, attempts are made to give substance to ‘autonomy’ for instance by emphasizing the importance of Bildung. But Bildung was a way of educating an administrative elite and of thereby securing a national culture. Aside from the fact that in an era of more than a thousand subdiscipines it is, in practice, an empty notion, it is a white, elitist conception untenable in an age of mass enrolment. Authors from the political left to the right discovered the obsoleteness of Bildung as an ideal in the 20th century. Gramsci noted with respect to the ‘humanistic programme of general culture’ that it was ‘doomed’ because it had been based ‘on the general and traditionally unquestioned prestige of a particular form of civilization’ (Gramsci 1971: 27) – a prestige no longer unquestioned. And in 1958, Helmuth Plessner explained the problematic situation of the Geisteswissenschaften (what else is new?) out of their obsoleteness now that the Humboldtian ideal had become outdated: ‘Die öffentlichen Institutionen des akademischen Praxis helfen also der geisteswissenschaftlichen Forschung und Lehre weniger als früher (…) In der Epoche des Massenstudiums kann es auch gar nicht anders sein. Humboldt hatte die vorindustrielle Gesellschaft mit ständischen Privilegien vor Augen, in der nur wenige studierten und der Bedarf an Natur- und Geisteswissenschaftlern überhaupt nicht zählte’ (Plessner 1985 [1958]: 170). In my view, whoever yells ‘Bildung’ in the current situation has no idea of what he or she is talking about – and this is typical of much current discussion: just because people work in universities, they think they know about universities; a fatal mistake many a social scientist will recognize from analysis in other domains as well. In effect, then, claims for autonomy and Bildung are often the guises under which a conservative clinging to privileges shows itself, perhaps not quite without false consciousness. Of philosophy, Jacques Derrida has said that it ‘clings to the privilege it exposes’ (Derrida 2002: 1-2; italics in original). We should, then, to paraphrase Derrida, undertake the effort to decapitalize elitist and overblown notions like Bildung.

Instead of focusing on internal democratization, we need a new and convincing, even a seductive narrative of the place of the university in democracy. What we need is a renewal of the public tasks of the university. That means we need a way of saying that democracy at large is helped by the existence of public universities. Neither state nor business are likely to have much interest in such a message. This is unfortunate, because democratic states should be more interested. One option would be to reverse the way in which the Dutch ‘science agenda’ is currently being formed. For a month, people can send in the questions they want scientists to answer through a web portal. That’s a bad way of making science public, because formulating questions is the hardest part even for scientists. More importantly it is a way of drawing the public in by keeping it at a distance. The reverse would be more interesting: have universities, faculties, and departments actively formulate the ways their work is relevant for publics – sometimes for publics that don’t even know they exist as a public. Have universities not merely ‘respond’ to a thing called ‘the public’, but let them make knowledge public by reflecting, always, on the public consequences of their work. Those building smart traffic algorithms might, helped by scholars from the social sciences and humanities, develop a view on the public benefits and dangers of their work (which decisions are tucked away in algorithms? Which options are off the democratic table in favour of technocratic management, such as ‘less traffic’?). Those working in financial economics should be engaged in debates with historians claiming their public uses lie in countering ‘short-termism’ (cf. Guldi & Armitage 2014). Such ‘views’ may be forms of dissensus, when scientists disagree. There’s nothing new in that (many a newspaper article has two scientists subscribing to opposing views), and it nourishes democracy. The question is, then, whether we can politicize science in democratic ways? Can we come up with ways to engage publics with the values at stake in our research and teaching? Mark Brown has argued for a democratization of science to the extent that scientific experts should be seen neither as technocrats nor as value-free but as representatives of specific publics (Brown 2009). Such are promising directions to take the current protests and struggles.

Let me end by briefly stating, for the sake of these struggles and without claiming exhaustiveness, what the public tasks of the university are as I see them. And let me add a few remarks on the consequences for the struggle over the university that I draw from them. They are fourfold:

- The provision of accessible education. This means no conservative reflexes about the ‘massification’ of the university. When higher vocational degrees are required even to work at the counter of the supermarket, it will not do to become exclusive. Likewise, we should stop investing in ‘excellent’ students. Politics should withdraw its claim to have a fixed percentage of students in honours tracks. Precisely these ‘excellent’ students are not the ones that need extra investing. We should also stop defining the contours of the university based on the choices of study of eighteen-year-olds. That we have done so up to now is a clear sign of a lack of idea of the university.

- The conduct of free inquiry. That means independence from state and market pressures. Since either one of these, often combined, fund research, this is of course quite impossible, but what I emphasize in it is the possibility of critique. Of course the very social sciences and humanities in favour of critique have abolished it for epistemological and other reasons, and of course ‘being critical’ has itself become a neoliberal value pur sang, but still, there should be critique that is more than ‘thinking out of the box’. But upholding free inquiry does not mean the conservative reflex of ‘autonomy’. It rather means reconstituting the role of the university in democracy as a whole.

- The provision of a knowledge archive. Universities have unique memory functions. But these should not be unchangeable. Ways of ‘publication’ – often in effect ‘privatization’ – should be reconsidered, and so should the set of disciplines offered. Without pleading for ‘interdisciplinarity’ as a way of imposing austerity, we need to consider whether the memory function of universities remains tenable with increasing disciplinary differentiation.

- The provision of public knowledge. This is perhaps the main challenge, especially for inward-looking discussions about internal democratization. The above remarks on the politicization of science pertain to the ways in which we might endeavor to make knowledge public, to thereby aid in the constitution of publics, and to thus give shape to a truly democratic function of the university. If we cannot find ways to do this, we will end up without convincing arguments for being publicly funded.

Coda

I’m writing this on an Apple machine, having just watched a BBC documentary on the disastrous working conditions in a Chinese Apple products assembly factory and the possibly worse conditions under which tin – essential ingredient for iPhones – is mined on the Indonesian island of Bangka. I’m struck by the outrage and anger I’ve witnessed in Amsterdam and elsewhere, which is inversely proportional to the apparent lack of anger I see the Chinese and Indonesian workers exhibit. Mostly, the Chinese appear too tired to be angry, and they fall asleep even during work. Many Indonesians have no choice but to risk their lives even in illegal tin mining. Meanwhile in Amsterdam and London hell appeared just around the corner. What is my point here? I think it’s this: our possible contribution – along with the contributions of journalists – to emancipatory politics lies in our efforts at connecting publics in the world. For instance, we may contribute, with knowledge of modes of production, the circulation of capital, the development of technology and the development and use of new materials, and the evolution of social movements, to the establishment of ways through which iPhone users are connected to iPhone workers other than the connections existing today. We might, in whatever limited ways, contribute to solidarity by helping constitute and connect people and publics. IPhone users and producers have a common interest in a dignified life, but as it stands, iPhone users are not connected. For that sort of contribution (and this is but one of very many examples), the type of democracy we need in our universities is not one of consensus, which is effectively a shield for conservatism, but one of contestation.

Referenties

Brown, M. (2009) Science in Democracy. Expertise, Institutions, and Representation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.Brown, W. (2015) Undoing the Demos. Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution. New York: Zone Books.

Derrida, J. (2002) Who’s Afraid of Philosophy? Right to Philosophy I. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Gramsci, A. (1971) ‘The Organisation of Education and Culture.’ In: Selections from the Prison Notebooks. New York: International Publishers: 26-43.

Guldi, J. & D. Armitage (2014) The History Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jefferson, T. et al. 1818. ‘Report of the commissioners appointed to fix the site of the University of Virginia, August 1, 1818.’ Journal of the House of Delegates of the Commonwealth of Virginia, Richmond: 10-16.

Kerr, C. 2001. The Uses of the University. Cambridge, MA: Harvard.

Plessner, H. 1985 [1958]. ‘Zur Lage der Geisteswissenschaften in der industriellen Gesellschaft.’ In: Gesammelte Schriften X. Schriften zur Soziologie und Sozialphilosophie. Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp: 167-178.

Roszak, T. (ed.) 1967. The Dissenting Academy, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

The Economist 2015. ‘America: A flagging model.’ In: ‘Special Report on Universities.’ March 28th: 14-18.

Noten

[1] This may be too much credit to what is but one protest in a string of protests though. Student occupations and protests more generally, at the moment of writing also occurring in Canada, have been occurring in 2005 and 2012 as well in the French part of Canada, after significant increases in tuition fees. This is where the ‘red square’ symbol, worn in felt pinned on the clothes of protesters, became popular among students (it was first used in a political context in October 2004). And in 2014, there were protests in Warwick, UK.Biografie

Willem Schinkel is Professor of Social Theory at Erasmus University Rotterdam and vice-chair of The Young Academy of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.